“I smelle a Lollere in the wynd!”

Chaucer’s Parson and the Lollard Sect Vocabulary

Both Walter William Skeat in his 1895 Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer and John Lounsbury 1892 book Studies in Chaucer: His Life and Writings state the sixteenth-century scholar John Foxe, in his 1563 Actes and Monuments of Martyrs, was the first to suggest that Chaucer’s Parson and perhaps Chaucer himself might be a Lollard. Looking closely at The Canterbury Tales, we can say clearly that their assertion is not true. The first person to suspect the Parson of being a Lollard was his fellow pilgrim Harry Bailey. “Sir Parisshe Prest,” quod he, “for Goddes bones/Telle us a tale, as was thi forward yore.” To which the Parson, quite prissily, responds: “Benedicite!/ What eyleth the man, so synfully to swere?[1] To which, the Host answered: “O Jankin,[2] be ye there?/I smelle a Lollere in the wynd!” (II 1166-1173).

So Harry Bailey, the quick-tempered drunk, rather than John Foxe, the abstemious martyrologist, was the first person to name Chaucer’s Parson as a Lollard; and the accusation, if we may call it that, was transmitted throughout the centuries and has formed a spirited debate. However, when taking a new perspective on a longterm debate it is helpful to formulate the questions that will guide the inquiry. To further investigate whether Chaucer’s Parson was a Lollard and, perhaps by extention Chaucer himself we need to determine who the Lollards were?[3] What were their beliefs? How might they have influenced Chaucer? Bailey’s declaration in the Epilogue of the Man of Law’s Tale, while a macabre joke about the scent of burned bodies on the wind wafting down to Southwerk from Smithfield, can leave us with even more questions. What might Harry Bailey know about the Parson? Or what might Chaucer want us to think Bailey knew, about the Parson’s underground religious leanings that he would accuse this seemingly upright churchman of heresy? What was it about the Parson and, by extension, Chaucer’s clear praise of him that makes Bailey suspicious?

Though Bailey’s tavern keeper’s back-slapping, bonhomie does not give him the most trustworthy voice in the Tales, the Host was on to something when he accused the Parson of Lollardy. Anne Hudson, in her seminal study, Selections from English Wycliffite Writing says that assigning the name “Lollard” is almost always hypothetical and we must work from inference (10). In addition, in her essay “A Lollard sect Vocabulary” Hudson argues that Lollards had a particular way of using certain words in their sermons, polemics and translations. We can use Hudson’s ideas of both informed extrapolation and a Lollard sect vocabulary as a starting point to explore how the description of the Parson and his dialogue in The Canterbury Tales strongly echoes Wycliffite complaints about the late medieval church. In examining the General Prologue description of the Parson using a detailed semantic analysis and comparison with fourteenth-century Lollard texts that circulated in Chaucer’s London, we find that Chaucer’s semantic choices puts the Parson firmly in the Lollard fold. Chaucer chooses from the Lollard sect vocabulary to create a character that lives the Lollard’s idea of vita apostolica. The Parson, and the Lollard sect vocabulary Chaucer uses to describe him outlines a man who is educated, poor, outspoken towards his betters, unwilling to curse for tithes, and provides the type of pastoral care advocated exclusively by Lollard texts.

Who Were the Lollards?

To first understand why Chaucer might characterize his Parson as a Lollard we need to briefly find out who belonged to the sect, what were their beliefs, and how did they advocate their cause. While a protracted description of Lollards in Chaucer lifetime is beyond the scope of the essay here, we can clarify our terms. What was a Lollard? Lollardy was the political and religious movement of the Lollards from the mid-fourteenth century to the English Reformation. Lollardy was supposed to have evolved from the teachings of John Wyclif, a prominent theologian at the University of Oxford beginning in the 1350s. Lollard demands were primarily for reform of the Roman Catholic Church. Lollards believed that priests should live the vita apostolic, that is live like Christ’s apostles, preaching the word without any personal gain.[4] Lollard doctrine taught that piety was a requirement for a priest to be a “true” priest or to perform the sacraments. Moreover, a pious layman had power to perform those same rites, believing that religious power and authority came through piety and not through the Church hierarchy. Lollardy emphasized the authority of the Scriptures over the authority of priests and to facilitate this they advocated a translation of the Bible into English. Lollard believed that the true Church was the community of the faithful, which overlapped with but was not the same as the official Church of Rome. (Some Lollards referred to the Pope as the anti-Christ.)[5] Likely what made a Lollard so “heretical” to the established English church and its hierarchy was that the Lollard preachers advocated apostolic poverty and taxation of Church properties.

How might Chaucer have heard Lollard sermons?

Now that we have established that Lollard ideas circulated in Chaucer’s London it is reasonable to ask, before we begin with a line by line analysis of the Parson, his description and the dialogue Chaucer gives him, how Chaucer might have known of Wyclif, Lollard writing, and the English translations of the Bible. For Chaucer to construct a Lollard Parson, he had to be familiar with their movement, their doctrine, their books, and the specifics of their reformist agenda. To explore this idea we must investigate what Lollard books circulated in Chaucer’s London and Kent? How might Chaucer have heard Lollard sermons? Who did Chaucer know who was active in Lollard politics?

As Ezra Kempton Maxfield states, in his 1924 article “Chaucer and Religious Reform,” that during Chaucer’s lifetime, Wyclif loomed very large on the fourteenth-century religious horizon (66). Wyclif’s honors at Oxford proclaimed him a brilliant churchman and throughout his life he remained a bold preacher. His books went everywhere and were still in circulation 100 years later. Maxfield is sure that it would be strange if we did not find some influence of Wyclif and the Lollard in Chaucer’s work (66).

Chaucer had many personal connections with prominent Lollards of his time. John of Gaunt, his brother-in-law, was a known Wyclif supporter for most of his life. In addition to Gaunt, Chaucer’s circle of friends and supporters included the known Lollards: Thomas Latimer, John Trussel, Lewis Clifford, John Pecke, Richard Strury, Reginald Hilton, William Neville, John Clanvowe and John Montague. These men were all mentioned in the Knighton and St. Albans chronicles as Lollards (Maxfield 69). Of course we cannot say with any certainty that Chaucer shared the religious beliefs of his family and friends, but the sheer number of men he associated with who were known Lollard sympathizers is something to consider.

What of the idea that Lollards and their beliefs were largely university wonks whose debates were confined to the colleges and halls at Oxford? How would Chaucer, who never attended university, have become familiar with Lollard thinking? Cigman, in her article “Luceat Lux Vestra,” argues that there is no useful distinction to be drawn between the “academic Wycliffite” and the “popular Lollard” (480). Wyclif’s ideas circulated well beyond the university. In addition, Lollards was seriously dedicated to preaching and teaching spread their interpretation of the Bible and what it meant to live a just life (482). Clearly, then, Lollard ideas were leeching out into the countryside and making themselves felt throughout the kingdom. The preachers who were moving around the realm proselytizing used written primers, sermons, glosses and after 1384, perhaps an English copy of the Bible as a teaching aid. How might Chaucer have known Lollard texts?

We will begin with what was one of the most controversial texts of its time—the translated English Bible. In the fourteenth century, the English church had a serious opposition to translating the Bible into the vernacular, though some powerful bishops did own copies of the Bible in French, most worked with the Latin vulgate.[6] Lollard “poor priests” may have been fortunate enough to have an English copy of the bible with which to work. [7] They might well have been marked to indicate the passages used in the service, which would be read in the vernacular.

Margaret Deanesley, in her 1920 book The Lollard Bible and Other Medieval Biblical Versions, states clearly that it was John Purvey[8] who wrote The General Prologue to the Wycliffite Bible which entered production around 1384 and edited the second version which was in ciruculation by 1394 (266). [9] It would not be too much of a reach to say that Chaucer, with his fierce dedication to translating works from Latin, Italian and French into English, would have been quite interested in the Lollard work on gospel translation.[10]

The Lollard Bible, however, was only one book. Lollards really made their mark through their itinerant preaching and their sermons. This leads us the question: how might Chaucer have known Lollard sermons? While we do not have access to Chaucer’s library records, nor do we know where he went on Sunday mornings, there was a clear time window in which Chaucer could have become familiar with the Lollard sermons. Ernest William Talbert, in his essay “The Date of the Composition of the English Wycliffite Collection of Sermons,” states that Wyclif and his poor priests were probably preaching a doctrine that smacked of heresy, likely without a license, as early as 1377 (467). Talbert gives five solid nodal points of history to contribute to dating the sermons:

- References to the papacy, since Lollard censured Gregory XI and in turn praised and castigated Urban VI

- References to the crusade of Bishop Spencer, proclaimed March, 1381

- Statements referring to the events of the 1370s

- Statements that indicate Oxford was the unmolested center of Lollards

- References to events after Wyclif’s death (468)

Taking these reference points into account, Talbert dates the Wycliffite sermons between 1377 and 1412 (473). So Chaucer, who likely died in 1401, would have had decades to hear and become familiar with Lollard theology.

So, the dates for the Lollard sermons and the two earliest translation of the Wycliffite Bible fit comfortably within Chaucer’s lifetime. The undocumented folk gossip about Lollard’s and their ways would have permeated London and fallen on the open ears of an observant poet like Chaucer. Therefore, keeping in mind Chaucer’s interest in translation, the high availability of Lollard texts and the high profile Lollards held in fourteenth-century society, we can construct an analysis of Chaucer’s Parson as a Lollard “poor priest.”

Literature Review of the Argument

As we can see from the type of texts that circulated in Chaucer’s London the broad stroke outline of Chaucer’s Parson in The General Prologue can overlap with some Lollard doctrine, so of course this is not the first essay to posit that the Parson was a Lollard. Scholars have debated whether Chaucer’s Parson had Lollard sympathies for centuries. As stated above, John Foxe, in his 1563 Actes and Monuments of Martyrs describes Chaucer as “a right Wicleuian” (Andrew 431). This debate picked up speed in the nineteenth century. J.H. Hippisley, in his 1837 book Chapters on Early English Literature, acknowledged that there was an inconsistency in “uniting a Lollard, an avowed despiser of pilgrimages, with a gay train of Catholic devotees” (155). Henry Hart Milman, in his 1857 book History of Latin Christianity; including that of the Popes to the Pontificate of Nicholas V, stated that “above all, the Parish Priest of Chaucer has thrown off Roman medieval sacerdotalism (367). Gotthard Lechler, in his 1878 book John Wiclif and His English Precursors, sought and found a number of parallels between the Parson and Wyclif himself. Lechler’s focus was on humility, virtue diligence, learning and the emphasis on the bible in preaching. At the end of the nineteenth century, Bernhard Brink, in volume two of his book History of English Literature, believed that Chaucer’s Parson represented the “ideal priest whom Wyclif had before his mind, and strove himself to realize” (144).

On the opposite side of the debate in the nineteenth century there was a vocal group of scholarly dissenters who did not believe that Chaucer’s Parson was a Lollard, nor did they believe that therefore, by extension, Chaucer himself could have had such religious and political leanings. Thomas Lounsbury, in his 1892 book Studies in Chaucer: His Life and Writings is quite clear in his section entitled “His Attitude Towards Wycliffe” that Chaucer was not a Lollard, nor did he construct his character of the Parson to be a Wycliffite (460-482). John Koch, in an 1879 review in Anglia emphasized that Chaucer was a good Catholic and that censure of the clergy was by no means an exclusively Wycliffite idea (540-544).

The discussion continued unabated into the twentieth century. Pamela Grey, in her 1923 section on Chaucer in Shepherd’s Crown: A Volume of Essays, refers to Chaucer’s Parson as a “Wycliffite priest” (82), Ezra Kempton Maxfield refuted that idea in 1924 in his PMLA essay “Chaucer and Religious Reform.” John Matthews Manly valiantly tries to compromise the two views in his 1928 edition of The Canterbury Tales by stating:

The Parson evidently represents Chaucer’s conception of the ideal priest. One of the pilgrims (II 1173) takes him for a Lollard and it is possible that John Wycliffe may have furnished some of the hints in the portrait. Chaucer was most undoubtedly closely associated with some of the leaders of the Lollard movement and the most striking and characteristic features of the Parson’s life and principles can be closely paralleled from the writings of Wyclif. (528)

Though Manly is one of the patriarch’s of Chaucer studies, his voice did not carry enough weight to silence the debate. In 1925, E.P. Kuhn, in his essay “Chaucer and the Church” posited that Chaucer himself kept company among highly orthodox men such as Henry of Derby, Sir Lewis Clifford, Sir John Cheyne, and Sir Richard Stury and those associations positioned him as someone who advocated reform of the abuses of the church, but were not Lollards. His conclusion is that Chaucer’s Parson was constructed as a response to a royal remonstrance in 1390 that advocated a return to Christ’s teachings without the threat of Lollard heterodoxy.

In addition, Chanoine Looten, in her essay “Les Portraits dans Chaucer: Leurs Origines,” correctly stresses that the Parson is not an itinerant preacher as Wyclif encouraged his followers to be. F.N. Robinson, in his edition of The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, is clear that the Parson should not be mistaken for a Lollard. “Wyclif, who died in 1384, presumably three or four years before Chaucer wrote the Prologue was repudiated as a heretic in his last days.” However, Robinson does concede that Chaucer would not have described his Parson the way he did had “reform not been in the air” (663-664).

The idea of Chaucer’s Parson standing in as a Lollard acquired an important advocate in Roger Sherman Loomis when he published his essay “Was Chaucer a Laodicean?” Loomis states that not only are the fellow pilgrims able to “smell” the Parson as a “loller,” but many modern scholars do as well (141). Loomis also points out the clear reference to the gospels so deeply emphasized by the followers of Wyclif and the accusation of Lollardy that goes undenied by the Parson. Finally, Loomis underscores that the two other “ideal” portraits in The General Prologue¸ the Knight and the Clerk were from the classes known to sympathetic to Wyclif and his teachings.

However, Boyd in his 1967 book strikes a more moderate tone. “There can be no reasonable doubt that some of Chaucer’s comments coincide with Lollard teachings, not all of which were heretical or completely so. Jill Mann, in her 1973 seminal study Chaucer and Medieval Estates Satire: The Literature of Social Classes and the General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales, is very clear that she considers the Parson the ideal of his social class (55). While Mann draws from a wide breadth of criticism about the medieval church to create her analysis of the Parson. In her book she states, “[w]hen we embark on a close reading of the General Prologue below we can see that the Parson shares a multiplicity of traits in common with Lollards, Lollard sermons contemporary to Chaucer. Perhaps we will continue to resist calling Chaucer himself a Lollard, but we can no longer ignore the parallels between the Parson and the ideal of the second estate.” Perhaps Malcom Andrews, in his explanatory notes about the Parson in his edition of The Canterbury Tales sums up the literature review best: “The disagreement [over whether the Parson was a Lollard] continues unabated” (433).

II

Line by Line Analysis of Parson’s General Prologue Description

In the previous sections we examined how Chaucer would likely have known and understood Lollards and their texts and the history of scholarly thought about the possible Wycliffian beliefs of Chaucer’s Parson. Now we will engage in a close reading of Chaucer’s Parson’s description in The General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales. In doing so, we will see that Chaucer’s overall semantic program in his interpretation of the Parson is to establish him as a Wycliffite preacher, using highly codified Lollard phrasing. Chaucer’s Parson preaches the gospel in English, and refuses to “glose” or to interpose a gloss or explanation and add any additional commentary of his own. Chaucer’s Parson is Lollard in his spiritual fastidiousness; he resfuses to curse for tithes, to get involved in the “business” of the parish, (making wills, overseeing “love days” etc.), to be deferential to people of higher social station. Through Chaucer’s deliberate omission, we find out the Parson does not encourage Mariolatry, hagiography or, quite ironically, pilgrimage.

A Poor Lollard Man

477 A good man was ther of religioun,

478 And was a povre Persoun of a toun,

In Line 477, Chaucer uses diction that indicates immediately that the Parson is a Lollard. As Doris Ives states, in her 1932 essay “A Man of Religion,” that the continual reoccurrence of this phrase in Lollard texts justifies the assumption that to Chaucer’s contemporaries the term “man of religion” applied to a secular priest and would have the significance of Lollard (145).[11] However, the phrase “povre Person”[12] was a signature Lollard phrase. Friends and foes alike of the Lollard movement described Lollard priests, as a“povre person.” The phrase itself was taken the English translation of Luke 7:22. The Latin vulgate bible uses the phrase “paupers evangelizantur.” In the first and second English translation of the Wyclif Bible, the phrase is translated to “pover men.” [13]

Chaucer likely knew there were a number of sociopolitical ideas embedded in the Wycliffite signature phrase “povre person” or its Lollard alternate “povre man.” Two of these sociopolitical ideas were particularly important when constructing his Parson character. The first is that the “povre person” travels the kingdom spreading the gospel in English. Winn, in his 1929 Wyclif: Select English Writings, cites Wyclif “alle Cristis disciplis traveiliden to bringe to oon men of þe Chirche, so þat þer shulde be oone heerde and oon flok” (31). The second of the sociopolitical ideals that help identify Chaucer’s Parson a Lollard is that the “povre person” calls attention to the abuses of the church: “We pore men, tresoreris of Cryst and his apostlis, denuncyn to þe lordis and þe comunys of þe parlement certeyn conclusionis and true this for þe reformation of holi chirche of Yngelond…” (Selections from English Wycliffite Writings Hudson 24). As we will see below, Chaucer’s Parson both travels around the kingdom and calls attention to the abuses of the Church.

While Chaucer’s Parson is not a “poor priest” in the sense that he is not an itinerant preacher, wandering the hills and shires of England, speaking the Wycliffite truth;[14] he does indeed have his own parish and his vocation is rooted there in his pastoral care. The phrase “pouvre person” would have been understood plainly in his own time that if the Parson was not a wandering Lollard preaching around the kingdom, he certainly travels far and wide throughout his own parish, preaching the gospel as Wyclif advocated his “povre person”s do. The Parson’s entire life stands as a foil to those who abuse their positions in the church. Right from the beginning of his General Prologue description, Chaucer draws from the Lollard sect vocabulary to indicate right from the beginning that the Parson is truly a Wycliffite “poor priest.”[15]

479 But riche he was of hooly thoght and werk.

As we know from the other religious pilgrims on the road to Canterbury, the Monk, the Friar, and the Pardoner, there were many ways a man could enrich himself in the nominal service of the church. Lollard polemicists and Wyclif himself had serious objections to ecclesiastic self-enrichment that went beyond the mainstream Reformist Movement in the fourteenth century. The goal of preaching, Lollards believed, was to spiritually enrich the priest and the laity. Preaching for material gain in any manner was forbidden to the Lollard. Wyclif, in his glossing on The Book of Revelation, puts it this way. Preachers “whoso prechiþ he seiþ þat he take here his mede of preching or of зifte wiþoute doubte he depryveþ hum self of ever lasting mede (Harley 1203 68 recto). In describing his Parson as “riche of thought and werk” Chaucer constructs his Parson as a man of whom Wyclif would have approved, a man enriched by his calling and someone who feels spiritually rewarded.[16]

In the first sentence of his description of the Parson, lines 477-479, Chaucer deliberately draws from the Lollard semantic field. He uses the same vocabulary to describe his priest as the first and second English translation of the Wyclif Bible; he is clear that his Parson does not turn a blind eye to the abuses of the church by calling upon the linguistic parallels found in The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards. Finally, Chaucer uses the Lollard lexical permutation of the word “povre” or “pore” in Wyclif’s glossing on The Book of Revelation as a way to emphasize the Parson does not preach for material gain.

A “Trewe” Priest

480 He was also a lerned man, a clerk,

Part of the spiritual wealth Chaucer describes for his Parson in line 479 comes from his education. While Lollard preachers saw as one of their main functions to preach to the laity in plain English, this did not necessarily mean that they themselves were uneducated. In fact, as we see in line 480, Chaucer’s Parson, “a lerned man, a clerk,” was an educated man who understood church Latin and had, as implied in the term “clerk,” studied at one of the major universities in the kingdom—Oxford or Cambridge. Despite their reputation as ill-manner trouble makers, many Lollards were highly educated men who saw it as their duty to teach the laity the knowledge that was usually the exclusive provenance of isolated university communities. Workman, in his biography of Wyclif, John Wyclif: A Study of the English Medieval Church, argues from this evidence that the depiction of the educated parish priest, described like Chaucer’s Parson, as the Lollard “povre persons” were men of culture (207-208).[17] What line 480 ultimately tells us is that Chaucer’s Parson spreads the previously sacrosanct privileged academic discourse throughout his parish, just as a Lollard would.

481 That Cristes gospel trewely wolde preche;

482 His parisshens devoutly wolde he teche. [18]

Just as Chaucer’s choice of “povre” to describe his Parson was deliberate allusion to Lollard preachers, the use of the word “trewely” in line 481 and Chaucer’s declaration that the Parson is a “trewe” preacher was a calculated semantic choice as well. Now, while praising his Parson, Chaucer could hardly have said “falsely would he preach.” That would not make sense. But the choice of “trewe” rather than any other adjective is significant. Chaucer would have known that the phrase “true priest” or fidelis euangelicus was another way that both adherents and enemies of the reforming movement used to refer to the Lollards in the fourteenth century. The number of instances Wyclif and other Lollards used this phrase in chronicles, sermons, and religious tracts of the time are almost daunting, so we’ll look at a selection of Lollard and anti-Lollard tracts.[19]

Lollard use of “trewe prest” orginates with Wyclif. Wyclif’s vocabulary in both his Florentum and his Rosarium presupposes a group of what he called familiares, a term which he uses interchangeably with “true priests” (Lollards and Their Books Hudson 28). When Wyclif uses the phrases “true men think” or “true men preach” it is a regular indication that the man is a Lollard (Lollards and their Books Hudson 28). The use of the adjective “trewe” to indicate a Lollard priest continues in, British Library manuscript Additional 15580, the late fourteenth-century manuscript containing the Thirty Seven Conclusions of the Lollards. The Conclusions state “I preie oure lord Jesu Crist for his endeles merci þat he suffer not þis orible evil to come to oure Cristene puple, but зeve grace to oure puple to lyve wel and mayntene goddis lawe and trewe prechouris þerof” (BL Add. Mss. 15580 86 verso). The Lollard sermon on II Corinthians 6:8 states: “as disseyveres and trewe men, for Goddis servauntis shulen have a name of þe world þat þei disseyven men, and 3it þei shulen holde truly þe sentence of Goddis lawe” (Lollards and their Books Hudson 167).

While Lollards advocated “trewe prechouris” or “trewe men” to roam the kingdom and preach God’s word, those who opposed the movement, such Henry Knighton,[20] in his Chronicle, uses the same phrase to describe them: “Similiter et caeteri de secta illa frequenter et absque taciturnitate in suis sermonibus et sermocinationibus inexquisite clamitaverunt, trewe prechours, “false prechours,” opinionesque mutuas et communes sicut unus ita et omnes” (Lollards and Their Books Hudson 166). To Knighton, a feverent opponent to the Lollards, “trewe prechours” are those who teach Lollard doctrine. So we can see that “trewe men” appears not only in the Latin and English works of those antithetical to the Lollard movement, but also in the teachings of Wyclif himself. Add to that the use of “trewe prechours” in the Lollard sermons and you have a phrase which has currency in fourteenth century public culture as a signature description of a Lollard.

In addition to being a man who “trewely wolde preche,” line 481 can also be read as Chaucer’s Parson preaches the true gospel. But what did the phrase “true gospel” mean in the fourteenth century? Or, atleast, what did it mean to fourteenth-century Lollards? The “true gospel” according to Lollards was the English gospel, available to every person who could speak English. Preaching was the highest calling of a Lollard priest and it is likely why the verb “preche” comes at the beginning of Chaucer’s Parson’s description in the General Prologue.[21] Now, certainly all parish priests, orthodox and heterodox, were required to preach. However, the verb, when used with the word “trewely” and applied to Lollard had a particular semantic resonance. It indicated Chaucer’s Parson was speaking the gospels in English. “Siþen þe Paternoster is part of Matheus Gospel, as clerkis knowen, why may not al be turnyd to Engliȝsch treweley, as is þis part?” (Winn 20). Chaucer wants the reader to know that rather than hoarding his knowledge as a clerical and masculine privilege, the Parson, like good Lollard “trewe prest” disseminates what he knows to the laity to help them avoid sin when they can and to repent after they realize their transgressions[1]. The Parson’s deep involvement in his community was also part of Lollard rejection of “private religion” that is living apart from the ordinary community of believers. By translating the gospel in to English and making a restricted text public, the Parson is directly espousing Wyclif’s ideas in de Officio Pastorali: “But þe comyns of Engliȝschmen knowen it best in þer modir tunge; and þus it were al oon to lette siche knowing of þe Gospel and to lette Engli ȝsch men to sue Crist and come to hevene” (Winn 20). The Parson’s deep involvement in his community was also part of Lollard rejection of “private religion” that is living apart from the ordinary community of believers.

In his second sentence, which runs from line 480-482, Chaucer’s use of the word “trewe” adds multi-lexical dimension to his portrait of the Parson as a Lollard. Lollards and their enemies used this adjective to note anyone who was an adherent of Wyclif. Furthermore, the word “trewe” tells us that the Parson spreads the previously sacrosanct prviledged academic discourse throughout his parish, in English just as a Lollard would.

Suffering and Tithing in the Parson’s Parish

483 Benynge he was, and wonder diligent,

484 And in adversitee ful pacient,

485 And swich he was ypreved ofte sithes.

In lines 483-485 Chaucer indicates that the Parson was tested many times during the course of his pastoral duties. That is to be expected. A rural parish priest was responsible for any number of obligations. He baptized, confirmed, married, and buried his parishioners. He attended to them during times of stress, he heard their confessions, exorcised their demons, supervised their tithing. When there was a labor shortage, he likely pitched in with a plough or scythe. Therefore, on the surface, there may not seem anything significantly heterodox in lines 485-487, that the Parson was “diligent and in adversitee ful pacient.” With some research, however, we discover a semantic overlap with the description in lines 483-485 with Lollard texts. British Library, Additional Manuscript 24202, entitled simply Priests, is a work by an anonymous late fourteenth-century Lollard. In the tract, the Lollard polemicist inventories the qualities of the ideal Wycliffite priest, describing him as a man who must “sufferyng in aduersite” (Cigman 489). Though we cannot be certain that Chaucer ever read British Library, Additional Manuscript 24202 specifically, we can be sure that the text and its ideas about Lollard priests circulated in religious and popular culture around London in Chaucer’s lifetime. We can perhaps extrapolate that Chaucer knew “sufferyng in aduersite” was a requirement for a Lollard priest and deliberately gave that quality to his Parson.

486 Ful looth were hym to cursen for his tithes,

In keeping with his reliance on Lollard texts to construct his Parson, in line 486 Chaucer plunges elbow deep into his description of the Parson as a Lollard who had serious objections to the orthodox church’s established practice of tithing.[22] The established practice of tithing in the fourteenth century was the medieval church’s version of the flat tax. Farmers had to offer a tenth of their harvest, while craftsmen and merchants had to offer a tenth of their production. Every medieval town and village had a tithe barn, a place where the merchandise and hard cash were collected to then be taken to Canterbury for division.

Lollards, however, had their own formula for tithing; one they felt honored the parish priests’ work and kept those less fortunate from going without. The Sixth Conclusion of the Lollards states:

Cristene puple enformid in goddis lawe by feiþful curatis owiþ for to mynistre and зeve to hem wilfulli necessaries of þis lif. And feiþful curatis owen to be apaied mekli wiþ þis portion. Þis sentence is open bi þis, þat Crist God and man and hise apostilis þat performide best þe werk of þe gospel and þe office of a curat weren apaied wiþ such portion. Þerfore a curat þat wole not be apaied wiþ such sustenaunce passiþ oure lord Jesu Crist. (BL Add. Mss. 15580 8 verso-9 recto).

Lollard’s felt their merit-based tithing system, as outlined in BL Add mss. 15580, was more fair and objected strenuously to the mandatory ten percent as a practice,[23] feeling with some justification that the very wealthy church did not need to take ten percent out of a peasant’s mouth to support a corrupt, worldly and often indolent clergy. An anonymous Lollard phrased it this way: “Bischops and archidekenes wiþ þer officials and denes shulden not amersy pore men; for þis is worse þan comyn robberye, siþen ipocrisie is feyned over wrong-taking of þes godis.” (Winn 82).

Still, tithing remained a regular, enforced practice in fourtenth-century England. The question was, how could the church, with no standing armed men make sure that everyone was paying their ten percent? They could not use force. Rather they used psychological pressure, the practice of cursing. In Chaucer’s lifetime cursing meant to pronounce a formal curse against, to anathematize, excommunicate, consign to perdition.[24] Cursing for tithes was an even greater anathema to Lollard. Wyclif himself said so in a number of places. In de Officio Pastorali chapters VI and VII he stated: “Also Crist and His apostlis neþer cursiden for þer dette and þey shulden be ensaumples to us. Whi shulden we curse or plete for hem?” (Winn 81). Wyclif also complains of “wereward curates that sclaundren here parischenys many weres by ensaumple of pride, envy, so cruelly cursing for tithes.” (Edited Works of Wyclif by Matthew 144). Lollard particularly disapproved of high ranking church officials in comfortable circumstances fining poor people. Again in de Officio Pastorali chapters VI and VII Wyclif is adamant on the point. “Bischops and archidekenes wiþ þer officials and denes shulden not amersy pore men; for þis is worse þan comyn robberye, siþen ipocrisie is feyned over wrong-taking of þes godis” (Winn 82). And in de Ecclesia Wyclif was clear that a priest’s desire to enforce tithes was itself a proof of his unworthiness (Workman 14). Lollards likely arrived at this perspective because there was widespread abuse of the practice; excommunication was used not just as a religious tool, but an often abused political means used to settle old scores.[25] Lollard teaching on this matter is clear; a priest should move his congregation by patience and other virtues and lives on alms as St. Paul did, and as the Parson in the General Prologue clearly does.[26] While the Parson did not have the power of excommunication himself, he was positioned and even advocated to turn “small tithers” over to the bishop for trial in the church court. When Chaucer says in line 486 that the Parson was “ful looth were hym to cursen for his tithes,” he aligns his Parson directly with Lollard thinking and writing on the subject. It would seem that rather than risk alienation of his parishioners by persecuting poor people for their poverty, the Parson works to keep the faithful connected to the overall religious life of the parish. We see Chaucer’s Parson then as a benevolent churchman, holding firm to the Lollard perspective on tithing and excommunication, contrasting sharply with the other clerics on the pilgrimage.

Lines 484-486 show Chaucer’s Parson as Lollard polemicists advocate: they suffer alongside their parishioners. Chaucer’s parson conforms to the Sixth Conclusion of the Lollards with respect to tithing. Finally, as Wyclif states in de Officio Pastorali, he refuses to curse the indigent for their lack of tithing. These lines lead us logically to the next, lines 487-490, where Chaucer describes the Parson as redistributing his own income to those in need throughout his parsish.

Offrying, Substaunce and Suffisaunce

487 But rather wolde he yeven, out of doute,

488 Unto his povre parisshens aboute

489 Of his offryng and eek of his substaunce.

The Lollard sect vocabulary in lines 487-489 give us further insight into the Parson’s character. Here, Chaucer gives us more detail on out how the Parson handled the finances of his parish, often a contentious subject and one that required real pratical skill. First let’s explore what Chaucer meant by “offryng” and “substaunce.” The “offryng” Chaucer mentions in line 489 was the voluntary contribution the parish gave to the village parson.[27] A priests’s “substaunce” (489) was his possessions, goods, or his earthly wealth. The Parson, like Lollard preachers rejected personal property—especially when that property conflicted with his pastoral duties. He was to live on the voluntary tithes and private alms he received. In BL Cotton Titus D. i, Wyclif explains how priests should manage their worldly goods “…clerkis moun have temporal godis bi title of almese, oenli in as moche as þei ben needful or profitable to parforme here gostlie office” (1 recto).

While adhering to the Lollard dictum to take only what he needed to perform his spiritual office, in line 489 of Chaucer’s General Prologue description, we discover that the Parson would take his own money from the offertory and from the small salary he received as parish priest and redistribute that money back into the community. This redistribution of resources was not part of the orthodox Church philosophy; it was a Lollard practice. In fact Wycliffite preaching is clear on how the parish priest should redistribute his wealth in a number of their tracts and polemics. In BL Add mss. 24202, in the tract on Miracles, the author states:

…and yif þes makers of ymagis þat stiren men to offer at hem seyen þat it is bette to þe puple for to offir her godis to þes ymagis þen to visit and hep her pore neзeboris wiþ her almes. (26 verso)

The tract on miracles is not the only text to address the redistribution of wealth in the parish from those who have to those in need. In the ninth sermon of Dominica ij post Octavam Epiphanie another anonymous Lollard explains that: “Furst techuþ Poul how þes preetis of þe puple schulde passion in ȝiftis of God þe comyns by þer good lif” (Hudson Sermons 513). Perhaps more importantly, the first article of the Conclusiones Lollardorum[28] states: Clerkis moun haue temporal godis bi title of almese oenli in as moche as þei ben nedeful or profitable to parforme here gostli office” (Compston 714).

So, in examining the Lollard sect vocabulary Chaucer uses in his General Prologue description of his Parson from lines 477-489, we have a poor Parson who will not curse for tithes, and who takes money out of the collection plate to giev to the needy in the parish—just the kind of financial advice Lollards give in their sermons and polemics. The description of the Parson as a man willing to distribute the parish’s resources to the needy is further confirmed in the next line.

490 He koude in litel thyng have suffisaunce.

A parson’s “suffisaunce” was the sum total of material possessions the village parson had to live on. The Lollard sermon Fifty of the Sunday Gospels is very clear regarding how priests should behave regarding their “suffisaunce.” “…hit falleþ not to Cristus vyker, ne to preetis of hooly chirche to haue rentes here on erþe; but Iesu schilde be þer rente, as he seiþ ofte in the olde lawe, and þer bodyly sustynaunce schulde þei haue of Godis part, of dymes and offryngus and oþre almes taken in mesure, þe whyche by þer hooly lyȝf þei abelden hem to take þus” (Sermons Hudson 452). It is not just the anonymous Lollard preacher who believed that priests should live within the means of their parish. The First Conclusion of the Lollards also indicates that a priest should live on the tithes willingly given by his parishoners. “Neþeles, clerkis moun have temperal godis by title of almese oenli in as moche as þei ben nedeful or profitable to parforme here gostli office”[29] This is exactly how Chaucer’s Parson handles the financial aspect of his pastoral care in his wide parish. He lives a measured life on very little material wealth, on what God sends him, just as the apostles did.

Lines 487-490 cover a wide swathe of description about the Parson. Chaucer uses these lines to solidify the connection his semantic choices have with the Lollard polemics. The Parson’s behavior parellels John Wyclif’s advice, in his gloss on Revelation, when advising how priests should manage their worldly possessions. Chaucer paraphrases the Lollard tract on Miracles, by describing his Parson as redistributing the tithes from the parish. The Parson’s treatment of his “suffisaunce” is directly in keeping with the Lollard sermons on the subject.

Moving About the Parish

491 Wyd was his parisshe, and houses fer asonder,

492 But he ne lefte nat, for reyn ne thonder,

Lines 493-494 tell us that the homes in the Parson’s parish were spread far apart and that did not stop him from carrying out his pastoral duties. This is a commendable character triat, but hardly exclusive to Lollard philosophy. We need to look deeper to find out what Chaucer was really indicating with his semantic choices here. In particular, that the Parson never left his parish in “reyn ne thonder.” While the word “thonder” may seem a simple reference to bad weather here, it functions as more than a meteorological term. Here Chaucer uses “thonder” to refer to the Pope’s excommunication of Lollards. In the Lollard polemic on Dominion, the Wyclif discusses the pope’s power to excommunicate. Lollards, of course, were particularly vulnerable to this threat. Wyclif himself and many other famous English Lollards were excommunicated.[30] Specifically, in Of Dominion, the Pope’s excommunication was said to have “þundured overe til Englond schulde fere ouere rewme” (Winn 63). The thundering papal bull of Lollard excommunication was a well documented event in England.[31] By using an important word in the Lollard sect vocabulary, Chaucer tells us even under the threat of the Pope’s thundering excommunication, the Parson does not hesitate to travel the parish and preach the Lollard gospel.[32]

493 In siknesse nor in meschief to visite

494 The ferreste in his parisshe, muche and lite,

495 Upon his feet, and in his hand a staf.

While it may seem a small detail, Chaucer’s specific use of the noun “feet” is noteworthy because Lollard writers, especially Wyclif himself, felt that the act of walking itself was a spiritually cleansing act. In his glossing on the Book of Revelation, Wyclif states “By þe feet been bytokened symple men in holi chirche þat ben in þe furneys of trewe labour and þerby clense hem of synne” (Harley 1203 3 recto) In addition to the Parson traveling the way a Lollard would, lines 495-497 are meaningful because of what is not said. The Parson travels with only a staff and nothing else in hand. This distinction is important; the Parson, as a true Wycliffite “povre person,” did not travel as mendicant friars were allowed to travel, with scrip, satchel and a helper. Satchels and scrips were vehicles to hold property and a way to take money and goods away from the congregation.[33] Chaucer’s Parson carries only a staff, just as the apostles did and the biblical symbol of the staff is clear. We are supposed to see Chaucer’s Parson as a Christ-like “good shepherd” as in the parable from John 10 1:18.[34] Wyclif, in de Officio pastorali also used this imagery often and potently.

In lnes 491-495 Chaucer portrays the Parson using coded lexemes from the Lollard vocabulary that circulated within Chaucer’s landscape. We find that Chaucer’s chooses deliberately from the Lollard sect vocabulary to create a Parson character that moves around his landscape living the Lollard’s idea of vita apostolica. Chaucer uses the word “thunder” not just as a meteorological term, but as a reference to Wyclif’s Of Dominion and the metaphorical description of the Pope’s anger at the Lollards. Chaucer’s Parson is cleansed spiritually through the act of walking as Wyclif describes in his glossing on the Book of Relevelation. The possession of a single staff while wandering the Parish, preaching the gospel in the vernacular underscores Chaucer’s Parson as a Christ-like “good shepherd.”

“Ensaumple,” “Taughte” and “Caughte”

496 This noble ensample to his sheep he yaf,

497 That first he wroghte, and afterward he taughte.

The Lollard-influenced semantic choices Chaucer made in lines 496-497 are a multi-layered. The idea that the clergy should function as a “noble ensample” of good behavior is explicitly stated in Conclusion III in the Thirty Seven Conclusions of the Lollards. “Prelatis and preestis as curates owen to sheewe to þe puple ensaumple of holi lyuynge and to preche truli þe gospel bi werk and word” (Compton 742). Living “bi werk and word” has within it embedded the Lollard idea of translating the bible and using it for the purposes of proselytizing.

At first, the link between right living and translating may seem unclear, but the fourteenth-century use of the word “ensample” ties right living and translating together because embedded in this idea of right living for the Lollard was preaching in English. Wyclif himself stated “For myche more meuiþ þe peple þe open ensaumplis of perfite and virtuous lijf of þe prechour þen nakid wordis only” (Cole 1145). What Wyclif means by this is that a priest should live a virtuous life, (both Wyclif and Chaucer use the same noun, “ensample”) and that virtuous life acts as a springboard for teaching the gospel in English.

Chaucer furthers his connection between the Lollard drive to translate and its link to the Parson with his use of the verb “taughte.” In choosing this word we see that semantic choice also lets Chaucer advocate for the Parson preaching the gospel in English. The most significant medieval sense of the word “taught” or “teach” is “to show (a person) the way; to direct, conduct, convoy, guide.”[35] Chaucer himself uses this sense of the word in The Nun’s Priest’s Tale “I shal my self to herbes techen yow/That shul been for youre hele” (VII line 129) The emphasis of directing and guiding and showing the way, as Chaucer uses it in The Nun’s Priest’s Tale and in his General Prologue description of the Parson, is a direct parallel to the Wyclif directives on why the bible should be translated. In Officio Pastorali, chapter XV, Wyclif uses the verb “tauȝt” in a highly specified way—to make the case for showing the faithful the way, guiding them to the true word, by translating the Bible.[36]

Whanne Crist seiþ in þe Gospel þat boþe heven and erþe shulen passe, but His wordis shulen not passe, He undirstondiþ bi His woordis His wit. And þus Goddis wit is Hooly Writ, þat may on no maner be fals. Also þe Hooly Gost ȝaf to apostlis wit at the Wit Sunday for to knowe al maner langagis, to teche þe puple Goddis lawe þerby; and so God wolde þat þe puple were tauȝt Goddis lawe in dyverse tungis. But what man, on Goddis half, shulde reverse Goddis ordenaunse and His Wille? (Winn 19)

By deliberately using the verb “taught” in his description of the Parson and linking that with the Parson as living example of Christian behavior, Chaucer is calling up this well-honed Lollard argument about teaching the Bible to the faithful in English.[37]

498 Out of the gospel he tho wordes caughte,

What Chaucer has begun in lines 496-497, he drives home in line 498, by emphasizing the authority of the gospel is a signature feature of both the Parson’s and Wycliffite thinking.When we examine the etymology of the verb “caughte” as Chaucer uses it provides critical insight into the word “caughte” as another reading of “translate.” One of the uses of the verb “catch” in The Oxford English Dictionary is “to be communicated, spread.” However subtle, line 498 gives the metalinguistic impression that the Parson Chaucer’s choice of the verb “caughte” indicates that his Lollard Parson is proselytizing the new, translated gospel. In catching the words, the Parson lays hold of the sentence or the sense of the vulgate and translates the gospels into English.

Though they are just three words from the Parson’s description in the General Prologue, “ensaumple,” “caughte” and “taughte” are highly charged Lollard vocabulary selections. The word “ensample” links living a righteous life with translating sacred texts into English. Chaucer furthers this connection by using the word “taughte” in the same way John Wyclif does in Officio Pastorali, to advocate translating the bible for the laity. Chaucer drives the message home by using the word “caughte” as another reading of “translate.”

Iren, Gold, Shite and Sheep

499 And this figure he added eek therto,

That if gold ruste, what shal iren do?

For if a preest be foul, on whom we truste,

No wonder is a lewed man to ruste;

And shame it is, if a prest take keep,

504 A shiten shepherde and a clene sheep.

In lines 499-504, Chaucer gives us some interesting analogies: gold to iron and cleanliness to shit. Line 500, “if gold ruste, what shal iren do?” is a loose paraphrase of Lamentations 4:1.[38] John Wyclif, in his glossing to the Book of Revelations, indicates that gold was analogous to the word of God. “Þe golden reed is holy write in whiche is goddis wisdam bytokeneþ bi þe gold” (Harley 1203 58 verso) Wyclif and Chaucer are using the same metaphor—gold is the word of God. If the Parson, as the vehicle for God’s word is a compromised messenger, the golden sacraments will be compromised.

The next analogy, “shiten shepherde” and “clene sheep” is derived, in part, from standard exegetical language. There is a long biblical tradition of glossing sin as excrement. “Clennesse” is often used as a metaphor for innocence, freedom from sin. However, Chaucer may have taken the idea of the “shiten shepherde” from the Lollard Sermon forty eight of the Sunday Gospels. In this sermon, Lollards specifically use the metaphor of “donge” to describe priests who have little to no pastoral calling and simply use their positions to enrich themselves. Parish exploitation may consist of bilking the parishioners for specious spiritual causes, or abandoning the parish altogether to a hired cleric and moving away to take a more lucrative position. Chaucer’s admonitory language, warning that a “shiten shepherde” will compromise the spiritual well-being of the flock reads like a condensation of Sermon 48:

Lord! Ȝif coowardyse of suche hynen [mercenary clergy] be þus dampnyde of Crist, how myche more schulden wolues be dampnyde þat ben put to kepe Cristus schep? But Crist seyþ a clene cause why þis huyrede hyne fleþ þus; for he is an huyred hyne and þe schepe pertene not to hym, but þe donge of syche schep, and þis donge sufficeþ to hym hoeuere þe schep faren. (Sermons Hudson 440)

While Lollards were not the only glossators to ever make use of the “shiten shepherde” metaphor, the parallel to how Chaucer describes his Parson is striking. Both the Lollard polemicists and Chaucer call shame on the priest who abandons his flock and will, therefore, himself be covered in the dung of the parishioners sins, as Chaucer so succinctly puts it, “a shiten shepherde”.

Chaucer uses tangible visual and olfactory nouns in lines 499-504. Doing so makes the poetry resonant on a sensory level. In addition, he chooses these particular nouns for their lexical overlap in Lollard polemics and sermons. John Wyclif wrote that that gold was analogous to the word of God. And Sermon Forty Eight of the Sunday Gospels uses the metaphor of “donge” to describe priests who have no pastoral care and use their positions to further themselves.

Right Living

505 Wel oghte a preest ensample for to yive,

506 By his clennesse, how that his sheep sholde lyve.

This is the second time Chaucer has used the word “ensample” in his description of the Parson. The poet used it above in line 505; he will use the word again in line 520 and repeat the concept in his closing line of 528. For a description of 51 lines that may seem repetitious. It is, however, repetition with a purpose.[39] John Wyclif, in his glossing on the Book of Revelations uses “ensample” in the same way that Chaucer does in his description of the Parson. “By Seynt Jon ben betokened gode placis þat han þe vois of þe gospels and undirstondent þat þe þretyng of þe dome betokened bi þe trumpe biddiþ hem do in werk al þat þey seen in holi writ and by good ensaumple teche oþers to do wel” (Bl Harley 1203 3 recto). Wyclif continues with the same message of “ensample for to yive” throughout his glossing of Revelations: “By his heer men of Critis religioun þat by holynes of good life ben white as wolle for bi gode ensaumple þei maken oþeres to do wel. By þe yзen ben betokened þe wile clerkis of holy chirche þat lernen oþers bi techyng and chausen oþers by sensaumple of her gode werkis” (Harley 1203 3 recto) Chaucer used “ensample” in 504 and draws on the concept of a clean flock in line 508. Lollard emphasized ther state of cleanliness over and over in their sermons and polemics. Þe Gospel on Feestis of Many Confessours states plainly in its rule for poor priests that “þus preestis shulden lyve clenli bi Goddis lawe, as þei diden first” (Winn 54).

In addition to repeating the word “ensample,” with the same emphasis that Wyclif does, Chaucer’s repetition of the word “clennesse” in line 506 is also reminiscent of Lollard texts. An integral part of living cleanly as a priest was rejecting the life of a “hyred hyne,” that is a mercenary. As the Lollard sermon writer describes in Sermon 48 above. So let’s take a moment here and explore exactly what a “hyred hyne” was and how it relates to line 507, “setting a benefice to hyre.”

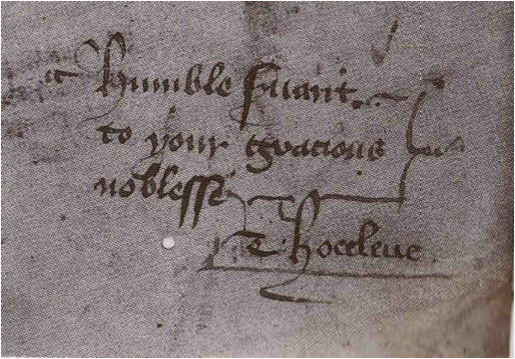

507 He sette nat his benefice[40] to hyre

The repetition of “ensample” and “clennesse” in lines 505-506 sect the reader up for line 507. By the fourteenth-century, especially after the upheavals of the Black Death, this was an increasing rarity. Chaucer’s Parson was remarkable because he did sublet his tasks to someone else, likely an outsider, hired to perform the duties that were rightly his. Now Chaucer was not the only fourteenth-century author to complain of this widespread, post-Plague problem. Even the normally conservative Hoccleve, in his Regiment of Princes, complained of it (lines 1415-1428). The number of chantry priests, probably in response to demand after the high death toll of the plague, was considered quite offensive to many of this time. Grace Hadow, in her book Chaucer and His Times, states that there was a common practice of paying poor and often illiterate priests to take charge of a parish while the vicar went to London and earned a handsome and easy living saying masses for the dead who had died with rich relatives and guilty consciences (198).[41]

However, the manner in which Chaucer describes his Parson, as a man who did not sublet his benefice, is directly in keeping with the Thirtieth Conclusion of the Lollards. In this Conclusion, Lollard theologians laid out strict guidelines for how a priest could live within his benefice: “Symple prestos of þe chirche þat han no beneficis by doom of þe chirche now owen to be apaied wiþ simple liflode and cloþinge in preiynge deuoutlie for hemsilf and þe puple and in vsing medeful werkis”(Compton 747-748). Chaucer’s Parson lives firmly within the limits of the Thirtieth Conclusion. And according to this Conclusion, the next lines repeat the Lollard motif of a good priest keeping his flock clean and remaining at home.

To London

508 And leet his sheep encombred in the myre

509 And ran to Londoun unto Seinte Poules

510 To seken hym a chaunterie for soules,

As stated above in the analysis of 503-504, the shit/sheep metaphor was a common construction for Lollard writers. Chaucer’s choice of the verb “encombred” is one that can be found in common Lollard sermons of the fourteenth century. BL BL Add ms. 41321 is a collection of unnumbered Lollard sermons. This is a tiny, portable book with well-thumbed pages—perfect for hiding up a sleeve from the prying eyes of an archbishop. We find a deliberate echo of Chaucer’s verb “encombred” here. Four recto of BL Add. Mss. 41321 states,” Þerefore, þei may more liзt hre a sonne be rerid of hire synne for þou зounge men be cumbrid with synne for frelnesse of her owen flessh зet if þei be priked with scharpe sentence of holi writ or be bete with þe yerde of God a non þei lene her cursed syne and ben sory þat þei have done amys”. BL Add ms. 41321 clearly echoes Chaucer’s General Prologue description of the Parson. Both state clearly that a flock will become encumbered in shit if a priest does not remain at home to keep them in line with holy writ. So that by line 509, Chaucer has made it clear that his Parson remains at home, preaching the gospel in English and maintaining a careful eye on his flock, deeply involved in the pastoral care of his parishioners.

While Chaucer’s General Prologue characterizations are known for their pithy commentary on the human condition and the medieval estates, lines 507-512 list what may appear to be, at first, extraneous. Here, Chaucer lists a number of things that the Parson does not do.[42] For example, in line 510 he tells us that, in accordance with Lollard beliefs, the Parson does not participate in the practice of chanting for the souls of the dead, “to seken hym a chaunterie for soules…” There were, of course, many things that the poet could have his Parson abstain from doing—all the sins, mortal or venal that the poet has distributed evenly among his other religious pilgrims. Yet why state so emphatically that the Parson does not sing masses for the souls of the dead? Compared to the other sins that Parson could have committed, what could really be the harm in singing in remembrance for those that died? The answer is found in the Conclusions of the Lollards. The Seventh Conclusion of the Lollards makes it clear that such behavior, deemed perfectly acceptable for other types of clergymen, is outside the scope of good Lollard behavior.

Þe seuenthe conclusion þat we mythtily afferme is þat special preyeris for dede men soulis mad in oure chirche preferring on be name more þan another, þis is þe false ground of almesse ded on þe qwiche alle almes houses of Ingelond ben wikkidly igroundid. Hwerfore us thinkis þat þe giftis of temperel godis to prestos and to almes houses is principal cause of special preyeris, þe qwiche is nout fer from symonie. (Selected Wycliffite Writing Hudson 26)

Given the ready availability of Lollard tracts, and the high publicity surrounding their conclusions, we can hypothesize that Chaucer has his Parson refrain from running “to Londoun unto Seinte Poules/To seken hym a chaunterie for soules,” because such a practice is expressly against the Seventh Conclusion of the Lollards.

511 Or with a bretherhed to been withholde;

In line 511, again using a negative construction as line 510; Chaucer tells us that the Parson does not work for a brotherhood. The noun that stands up for attention in this phrase is “bretherhed.” What was a “bretherhed” in Chaucer’s lifetime? It’s clear from the context that Chaucer is describing another way a parish priest could abandon his duties is to leave his benefice and take a more lucrative position somewhere else but what did that entail? John Tatlock, in his 1916 essay “Bretherhed in Chaucer’s Prologue,” tackled this problem head on.[43] Rather than gloss the word as is usually done, to indicate that Chaucer’s Parson could have abandoned his parish for more lucrative work within a monastery, a religious guild, a merchant’s guild that hired priests for religious observances, or perhaps even a chantry house singing masses, Tatlock describes a ‘bretherhed” strictly as a guild (140). Guilds had a long record of employing secular religious men for the spiritual good of their mystery.[44] The duties of such a position would have been light, particularly in comparison with those the Parson actually performs in his parish. A parson employed by a “bretherhed” would have very few duties. He would have chanted masses for the deceased members of the guild said a twenty minute service for those alive at the quarterly guild meeting, perhaps given a reading at ceremonial dinners. This would have left him time and leisure to engage in other pursuits or to take on other jobs. Lollards objected to this practice because it contributed to absenteeism and simony which we will discuss below.

Chaucer’s choice of the verb “withholde” in line 511 this phrasing is also an interesting one and it has been glossed in many ways: maintained, kept, or held. Chaucer in The Tale of Melibee, uses it to mean “engage for a certain service” (Tatlock 141). Therefore, the line tells us that the Parson, though he could have gone to London for more lucrative and perhaps more enjoyable employment, remained in the parish. That makes line 512,

But dwelte at hoom, and kepte wel his folde,

almost redundant. Why does Chaucer use so many different phrases in his normally concise General Prologue description to tell us that the Parson remained in his parish? He does so because two of the Lollard causes célèlebres were absenteeism and pluralism.[45] Both absenteeism and pluralism in poor, rural districts such as Chaucer’s Parson’s were fed by the easy opportunties that chantry work in a metropolitan area could offer. Some livings that had priests away praying in urban chantries rarely saw their resident priest and suffered accordingly from the spiritual deprivation of guidance and the organizational power of the clergy to make things better in the village during times of privation.[46] The Lollard polemic that is BL Add mss. 24202 is quite clear in its objection to the practice: “He is expresse forsworn for Crist put hym in þe state where ine he shulde more charge gostli profite þan erþliche and þerfore sey þe rewle of þe apostelis þat neþir bischop, prest, ne deken take upon hem secular curis and yif þei don, þei be putt down” (7 recto). In particular, priests practicing pluralism for the purpose of singing chantries was such a problem in fact, in de Officio Regis, Wyclif demanded the destruction of all “chantries, abbeys and houses of prayer and the restoration to the “poor men and blind, poor men and lame, poor men and feble,” and to the state all the goods that were really theirs (Workman 97). While neither Chaucer nor his Parson go as far as Wyclif does in advocating a redistribution of the wealth generated by the prayers for the dead to those in need, the Lollard objection to having parish priest leave their livings to sing in chantries is quite clear.

Lines 505-512 are loaded with Lollard lexical terms that find direct parallels in two Lollard texts, The Lollard polemic that is BL Add mss. 24202, A Tretis of Prestis, and de Officio Regis by John Wyclif. In lines 505-512, Chaucer establishes that his Parson lives by example and refuses to leave his flock “encombred” in the filth of someone hired to minister to his benefice. Chaucer deliberately breaks with his normally pithy ability to describe his characters and gives a list of things the Parson does not do—abstaining from behavior that Lollards object to, singing for the souls of the dead guild members, leaving his parish behind to take up a privileged position in a “bretherhed,” and abstaining from the practices of absenteeism and simony.

Wolf and Shepherd

513 So that the wolf ne made it nat myscarie;

514 He was a shepherde and noght a mercenarie.

While lines 511-512 deal with the very practical concerns of tithes, pluralism and absenteeism, in lines 513-514 Chaucer switches to more metaphorical language, using the metaphor of the devil as wolf and the parish priest again as shepherd. The image of the wolf in scripture originated in the gospels of Matthew and John.[47] In the English Wycliffite sermons, the gloss on Matthew Seven expands on this metaphor: “And by þis fruyt may men knowen þe falshed of þes woluys; for we schal wyten as by byleue þat louyþ more mannys good þan he loueth helþe of his sowle he is wolf and fedes child,” (Hudson Sermons 253-254). The metaphor originated with the gospels and was adopted by many of the early church fathers; many medieval writers make the metaphor of parson as shepherd and devil as wolf central to their expositions on the bible. Lollards were no exception. The translation of the first Lollard Bible, BL Add. Mss. 15580, translates John 10:11-18 in the following way.

I am a good shepperde. A good shepperde ȝeveþ his lyf for his sheep. But an hyrid hyne, and þat is not þe shepperde, whos ben not þe sheep his owne, seeþ a wolf comyng, and he leeuiþ þe sheep and fleeþ, and þe wolf rauissheþ and disparpliþ þe sheep.

The English translation,“hyrid hyne” in Matthew chapter seven is translated from the noun mercinarius in the Latin vulgate bible. Mercenarius is also nearly identitical to Chaucer’s use of the word “mercenary” below in line 516. The disparaged practice of hiring someone to look after the congregation appears in Lollard texts as well. In Wyclif’s gloss on Revelations, Wyclif breaks from the discussion of Job to say “Summe he seiþ ben hirid men, þe whiche sechen зiftis bi seyngis bi false relikis bi seelis and bi lettris and by false myraclis þat þei bigyle men lo for to gete her þing from hem unto hem” (Harley 1203 88 recto). The placement of the “hyred hynde” phrase so prominently in both the description of the Parson and in Lollard texts argues forcefully for reading Chaucer’s Parson as a Wycliffite. In fact, the metaphorical language Chaucer uses in lines 513-514 is not for poetic purposes alone. The metaphors of the wolf and the shepherd are part of the Lollard sect vocabulary that Chaucer deliberately mines for his description of the Parson.

Speaking Like Lollard

515 And though he hooly were and vertuous,

516 He was to synful men nat despitous,

517 Ne of his speche daungerous ne digne,

Chaucer’s emphasis in line 515 on the Parson’s virtuousness certainly makes him distinct from the other pilgrims, but the real test of the Parson’s mettle would have come from how he handled the reluctant, recalcitrant, and sinful in his wide and far asunder parish. In lines 516-517 Chaucer tells us that he neither was not “despitous,” spiteful, “daungerous” (meaning overly fussy), nor was he “digne” or prideful. Let’s begin at the last adjective here, “digne.” Pridefulness of the clergy was something that the Lollard strenuously objected to. It was part of their overall program of purging the church of worldly clergy, highly invested in their own prestige and social position. Wyclif, in his gloss on Revelations states “Þe þridde part of þe chirche is seid to be in the feld for laboris comounly make þei not þe þridde part of þe chirche and turne þei not aзen to kepe þer worldly godis for dred of an anticritis curs” (Harley 1203 96 verso). Emphasizing that the Parson was not prideful makes it clear that he was living within the boundaries of Wycliffite self-effacement.

The word “despitous” means the Parson was not merciless, difficult to approach or distant. Chaucer’s recitation here in lines 516-517 of everything his Parson is not finds greatest resonance with the Ninth Conclusion of the Lollards. The Ninth Conclusion states clearly that the parish priest has a responsibility to his congregation to be not only free from sin, but to be approachable, a real resource for the community. “So it is perilous to an unkunnynge man eiþer simple lettrid man to knouleche his sinnis and privy worchingis of God in his soule to a preest unfeiþful of lyuynge, unkunnynge of goddis law and a couetous preest and proud and contrarie to jesu crist” (Compton 743). This quote tells us an ignorant lay person is in a vulnerable position, particularly when their parish priest is ignorant, greedy or proud; a parishioner was really at the priest’s mercy. In his accessiblility, Chaucer’s Parson is in compliance with the Ninth Conclusion of the Lollards.

Techyng, Ensaumple and Bisynesse

518 But in his techyng discreet and benygne.

519 To drawen folk to hevene by fairnesse,

520 By good ensample, this was his bisynesse.

While discussing how the Parson satisfied the Ninth Conclusion, Chaucer phrases lines 516-517 in the negative, discussing who the Parson is not. However, lines 518-520 Chaucer leaves behind his cataloguing in the negative regarding what the Parson does not do, and moves on to discuss the specifics of what the Parson does do as part of his pastoral care. Let’s begin with the word “bisynesse” in line 520. In the fourteenth century, “bisynesse” could mean any activity in the parish. For instance, in the General Prologue, we find Huberd busy arranging marriages and adjudicating at love-days. The Monk handles disputes regarding wills and other legal documents. The Prioress refines and displays her courtly manners. Lollards, however, had a different viewpoint on what was the clergy’s business. Around 1380, Wyclif stated that “Cristis bysynesse in prechynge, ”[48] believing that preaching “bisynesse” keeps priests from robbing the flock like the Monk and the Friar do. The XX Sermon, continuing the metaphor that Chaucer also chooses for his Parson, that of shepherd to his sheep, clearly states:

Þe sixte seruyse takiþ he þat is aboue in bussynesse, as ben curatis of þe puple, oþur hyere or lowere. And alle þes prelatis schulden be bussy to kepe þe schep þat God haþ ȝouen hem. And here þenken monye men þat, fro þis staat was turnyd to pruyde, þei ben clepud prelatis and borun aboue by wynd of pryde; and þei be not aboue god, but more foolis þan þer suggetis; and þer bussynesse is turned to pruyde and to robbyng of þer schep. (Hudson Sermons 514)

Chaucer’s Parson conforms to what is outlined in the XX sermon, eschewing the type of “bysynesse” attributed to the Monk and the Friar and concentrating on the spiritual needs of the parish.

Snybbing

There were, however, boundaries to the Parson’s loving tolerance as Chaucer outlines in lines in lines 521-523.

521 But it were any persone obstinat,

522 What so he were, of heigh or lough estat,

523 Hym wolde he snybben sharply for the nonys.

Lines 521-523 tells us that while the Parson lives up to what is expected of him as Wycliffite parish priest, he has expectations of his “schep.” Lollards, more than any other fourteenth century religious sect, were known for their frank criticism. (Their readiness to ignore social order and lecture their “betters” was one of the reasons why they had so many enemies.) The Thirty-Sixth Conclusion of the Lollards states their position clearly “Þerfore no prelate mai please wolvis; and þe flockis of sheep for whi a soule bounde to erþli persons lesiþ þe mynde of lippis. Þat is to seie, a prelat mai not please togider tirauntis and gode, symple men. A man bounde to erþli covetise lisiþ mynde to speke up profitable truþe for iust men and to repreve tirauntis and extornoneris” (BL Add mss. 15580 75 verso). Therefore, it isn’t surprising that Chaucer tells us the Parson is direct in his censure of the unrepentant, whether “of heigh or lough estat,” that he “wolde he snybben sharply for the nonys”.

This directness is not a unique character trait of the Parson. Wyclif makes it clear in his treatise Þe Grete Sentence of curs Expounded that reproving worldly men for their sins is one of the pastoral duties of all Lollard poor priests: “…our clerkis [poor priests] shullen not fynde but povert, mekenesse, gostly traveile and dispisyng of worldly men for reprovyng of here synnes” (Winn 34).[49] Chaucer is likely drawing on this well-known trait of Wyclif and his followers when he describes his Parson as direct and forthright in his criticism of lapsing parishioners.

Lines 521-523 tell us that the Parson pays special attention to those “obstinat” parishioners. To be “obstinat,” was to hold an opinion despite argument, persuasion, or entreaty. Chaucer has chosen the adjective “obstinat” with deliberation and care because the obstinate were a particular problem for the Lollards. Lollards advocated hose parishoners who held opinions contrary to Lollard theology, were to be treated as heretics. The Thirty-Seventh Conclusions of the Lollards, clearly states that Lollard preachers must educate the parish and “techen errour in dede aзens Cristene feiþ. And if þei don þus obstinatli or mayntenen þis errour stidefastli, þei ben eretikis” (BL Add mss. 15580 4 recto). In 1395, John Purvey, one of Wyclif’s poor priests and until recently thought to be the translator of the early Lollard Bible[50] stated, “Þough it be leful in caas to werre and sleen euele cristene men obstinat in synnis.”[51] While the Parson does not go as far as Purvey in advocating the death penalty for the recalcitrant of his parish, Chaucer tells us he “wolde snybben sharply for the nonys.” What does that mean, exactly?

“Snybben” meant to reprimand, rebuke, or to check sharply.[52] To snyb someone, man had to be direct in his censure. In fact, the practice of “snybbing” or reproving, such as Chaucer’s Parson does, was integral in spreading Lollard beliefs throughout the social spectrum. “Snybbing” was so important that one of the Lollard Conclusions is devoted to just this type of prosteletyzing. The Eleventh Conclusion of the Lollards states clearly “Þe office of þe king and of þe seculer lordis which is founden sufficientli in holi scripture of þe olde and þe newe testament owiþ to be magnified excellentli in repreuynge þe errouris and wrongis whiche þe king and lorids don in suche officis agens þe lawe of god” (Compton 743). The Parson’s willingness to criticism regardless of the social consequence of others is not just a personality quirk unique to him. It marks him clearly as a Lollard.

The ability to stand up to someone of high social rank also helps the Parson avoid what Lollards considered “þe þridde manere don men symonye bi tunge,” (Winn 78) as described in Þe Grete Sentence of Curs Expounded. Chaucer’s Parson avoided, as good Lollards did, “þat neiþer ȝeven gold ne servyce to lordis, ne prelatis, ne mene persones, but bi flateryng and preier of myȝty men comen to benefices.” (Winn 78) In fact a Lollard’s known contempt for the powerful in the world was what made them a model for the rest of the community. It isn’t surprising that Chaucer tells us in line 524 that “A bettre preest I trowe, that nowher noon ys.”

Lines -524 are right in Lollard sect vocabulary terms and concepts. In these lines we find out that Chaucer’s Parson cherry-picks words and beliefs from the Conclusions of the Lollards to finalize his description. Specifically, he uses “despitious,” “obstinate,” and “snybben,” to make sure that the reader knows what the Parson’s reformist affiliations are.

525 He waited after no pompe and reverence,

526 Ne maked him a spiced conscience,

In lines 525-526 Chaucer emphasizes again that the Parson “waited after no pompe and reverence.” As stated above, that fits with his Lollard disregard of social consequence. But what does it mean that the Parson “Ne maked him a spiced conscience”? A “spiced” conscience means a scrupulous conscience. Line 526 has been translated and understood in a number of ways: that the Parson was not hung up on the ceremony of his office, that he was reasonable in dealing with is flock, that he had an open heart, or that he was not easily aroused to moral indignation (Benson 819). The Parson was a man not easily surprised by the sins of his flock, and was understanding of the human propensity for sin. This sanguine approach to the inevitable transgressions fits in with the Lollard sermons of the fourteenth century.

Finally, we can say that to the average, god-fearing medieval person, their parish priest stood as the gatekeeper between eternal damnation and eternal life. If he were in the parish and available to administer the sacraments, teach the gospel and say mass, the parish likely felt great comfort: “It is a greet relevyng fo bi of his disese when the sunne is goo don and þe derknesse of nyзt is come” (BL Add. Mss11 recto).

If, however, he was a sinful man, negligent, or absent, the entire parish would have felt spiritually under threat. “but whan þe nyзt of ignorance of Goddis lawe is come to any such goostli like man þane he is gretli disconfortid for defaute of good ensaumplis. (BL Add. Mss 11 recto) BL Add ms. 41321 is clear that a good Lollard preacher draws his flock to him by acting as a living example to the community. “It suffrireþ noзt ynow to prests to preche trueli þe word of God but also with ensaumples of god lyfe to go fore. “I darwe þe peple aftir hyre and þerfor þese two offices: truþe of preching and good liyf clepeþ Crist his true prechoures, salt of þe erþe and lyзt of þe world.”

The collection of his qualities, when examined in detail, makes the Parson, the perfect Lollard preacher. It is why Chaucer is able to say:

- But Cristes loore and his apostles twelve

- He taughte; but first he folwed it hymselve.

Conclusion